Stanley Kubrick and the SOE

Guy Woodward investigates an unrealised SOE film project

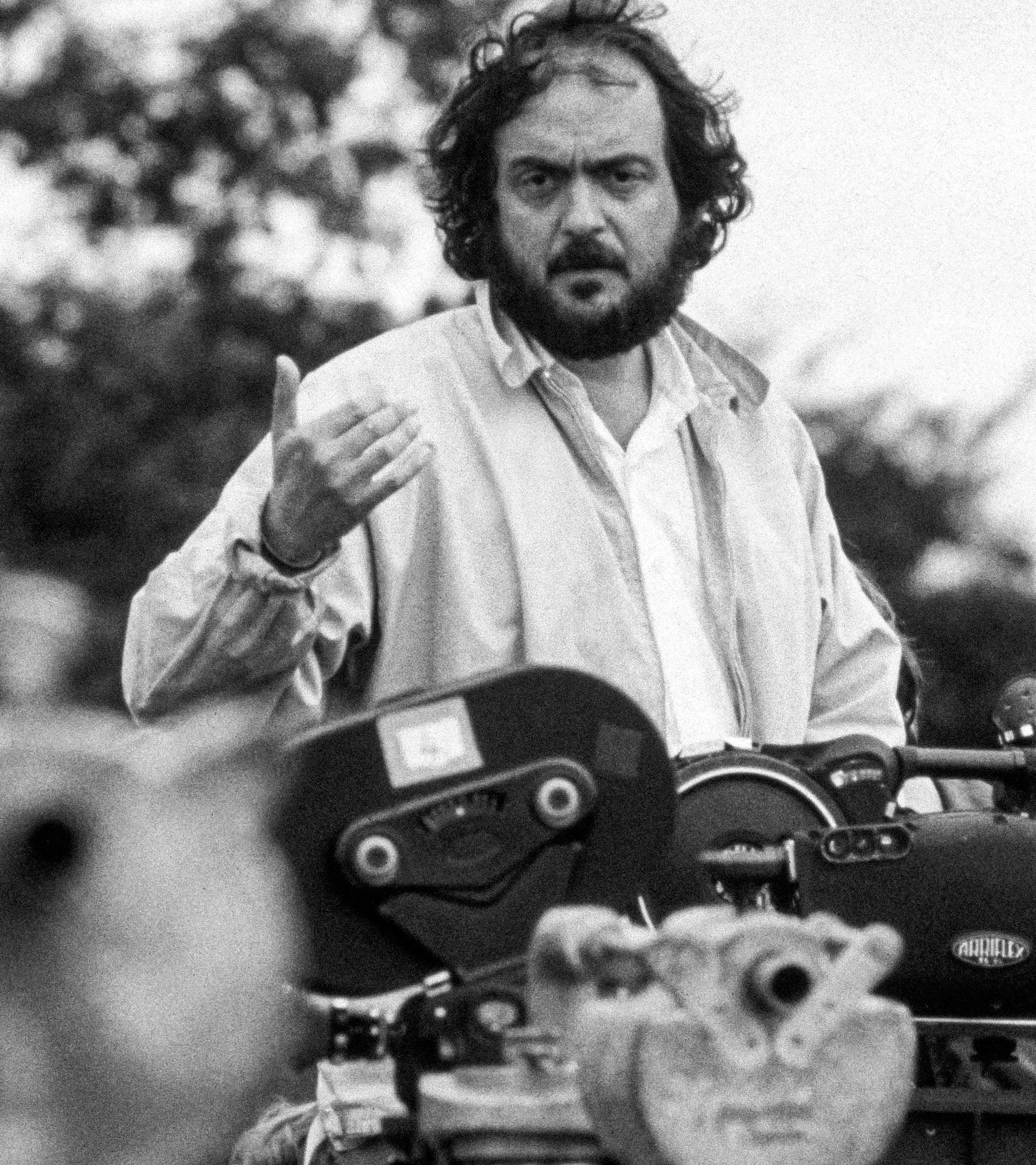

Stanley Kubrick was one of the most influential film directors of the twentieth century, responsible for a string of films addressing modern warfare: Paths of Glory (1957), Dr Strangelove (1964) and Full Metal Jacket (1987). This post explores Kubrick’s extensive interest in the Special Operations Executive, and how the director pursued John le Carré in the hope of collaborating with him on a film about treachery and deception in the SOE.

In his 2016 memoir The Pigeon Tunnel, le Carré recalled that Kubrick suggested that le Carré ‘should write him a Second World War spy movie set in France and based on the rivalry between MI6 and SOE.’ Le Carré writes that ‘I said I’d think about it, thought about it, didn’t like it and declined.’[1] This exchange appears to have taken place in the late 1980s, after Kubrick had finished making Full Metal Jacket and shortly after his fruitless attempt to adapt le Carré’s 1986 novel A Perfect Spy, which had already been optioned by BBC TV. Upon discovering this Kubrick apparently offered to direct the series for the BBC, but according to le Carré the corporation were wary of the director’s reputation for budget and schedule overruns; in the end the 1987 adaptation was directed by Peter Smith.

The MI6/SOE project Kubrick had in mind centred on the story of Henri Déricourt, a former airline pilot, and a French resistance leader and SOE agent who ran the executive’s Farrier network in northern France, organising the arrival and dispatch of agents by plane in 1943-44. Following the destruction of the Prosper network by the Germans in 1943, after which dozens of SOE and French resistance agents were executed and imprisoned, Déricourt was suspected of being a double agent. After a number of accusations made by French fellow agents, Déricourt was recalled to London in February 1944. Although he received strong support from senior officers in SOE’s F Section – notably including its head, Maurice Buckmaster – it was decided that he would not be allowed to return to the field.[2]

Investigating the events after the war, F Section’s Vera Atkins interviewed captured German intelligence officers who confirmed that Déricourt had indeed been working as a double agent, passing on information and documents which helped the Germans to capture and interrogate SOE agents. At his trial for treason in Paris in 1948 Déricourt insisted that his contacts with the enemy had been made in the service of the Allies; giving evidence in his defence the deputy head of SOE’s F Section, Nicolas Bodington, confirmed this version of events and Déricourt was acquitted.

Déricourt’s story has intrigued historians over many decades. In the 1950s the author Jean Overton Fuller interviewed him for her book Double Webs (1958): Déricourt admitted handing over documents to the Gestapo but claimed that he was acting on orders from a higher authority than SOE in London. In A Life in Secrets (2006), an investigation of Vera Atkins’s activities during and after the war, Sarah Helm suggests that the revelations in Fuller’s book spawned a conspiracy theory ‘that Déricourt himself was planted inside SOE by MI6. Perhaps MI6 was using Déricourt to keep tabs on the SOE camp and to further its own plans to deceive the Germans.’[3] Thirty years after the publication of Fuller’s Double Webs, Robert Marshall’s All the King’s Men (1988) had appeared to confirm this theory, alleging that Déricourt had been infiltrated into SOE by the deputy head of MI6 Claude Dansey.

Kubrick optioned All the King’s Men in August 1989; in addition to this agreement his archive at the University of the Arts London (UAL) in Elephant and Castle, London, also contains an annotated copy and photocopy of the book.[4] The extensive annotations and highlighted sections suggest Kubrick had a developed a sophisticated understanding of the various organisations, networks and agents under discussion.[5] Kubrick was also a keen reader of Fuller’s work: his library includes a copy of her book Double Agent? (1961), the revised edition of Double Webs, and her 1989 book Déricourt: The Chequered Spy in both published and draft form. All have been annotated by Kubrick; on some pages he appears to take issue with some of Fuller’s conclusions.

Beyond the Déricourt controversy, Kubrick’s specific interest in SOE and wartime special operations is indicated by a further series of relevant books in his extensive library at UAL. In the catalogue these are categorised with many other books addressing the Second World War, the Nazis and the Holocaust under ‘Aryan Papers’, in reference to another unrealised project of Kubrick’s to film Louis Begley’s Wartime Lies (1991), a novel of the Holocaust in occupied Poland: Jan Harlan writes that Kubrick had been searching ‘For decades […] for material that might allow him to make a film about the Holocaust.’[6] Filippo Ulivieri similarly suggests that the ‘Aryan Papers’ project is just ‘the tip of an enormous iceberg that floated around the director since the 1950s’.[7] Kubrick’s interest in British covert operations also stretched back over at least two decades: a copy of Airey Neave’s Saturday at M.I.9 (1969), a history of British underground escape lines in northern Europe in 1940-45, is dated inside the front cover: ‘Stanley Kubrick 16 February 1970’.

Furthermore, nearly two decades before that, Kubrick’s first feature film Fear and Desire (1952) involves a scenario not dissimilar to many covert operations narratives. The film follows four soldiers whose plane which has crashed over enemy territory during a war between two unnamed countries. Attempting to make their way back to base through a forest, the soldiers conduct a raid on an enemy base in search of food, killing the soldiers there; two of the party later assassinate an enemy general and escape using a stolen aeroplane.

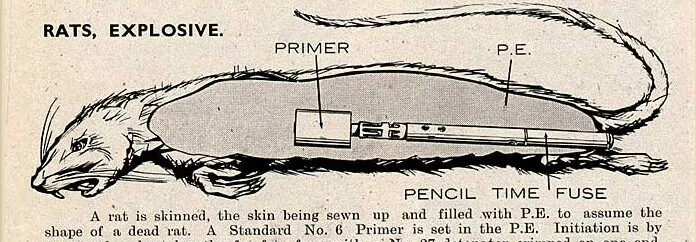

The SOE-related books in his collection include former agent J.G. Beevor’s historical memoir SOE Recollections and Reflections: 1940-1945 (1981); Buckmaster’s memoir They Fought Alone: The Story of British Agents in France (1958); Ewan Butler’s Amateur Agent (1963), a memoir of Butler’s experiences in SOE in Cairo and Stockholm; E.H. Cookridge’s popular history Inside SOE: the Story of Special Operations in Western Europe 1940-45 (1966); M.R.D. Foot’s official history SOE in France (1966); Józef Garliński’s Poland, SOE and the Allies (1969); Clandestine warfare: Weapons and equipment of the SOE and OSS (1988) by James Ladd and Keith Melton; Bruce Marshall’s The White Rabbit (1952), the story of SOE agent F.F.E. Yeo-Thomas’s mission to France and subsequent capture and interrogation by the Gestapo; Jerrard Tickell’s enormously popular Odette: The Story of a British Agent (1949), a biography of SOE agent Odette Hallowes, who parachuted into France in 1942 and survived capture and incarceration by the Germans at Ravensbruck concentration camp. A film based on Tickell’s book starring Anna Neagle and Trevor Howard was released in 1950.

Kubrick’s library also features Between Silk and Cyanide (1998), a memoir by SOE codemaker Leo Marks, which addresses at length the penetration of SOE’s network of agents in the Netherlands by German intelligence (the so-called Englandspiel operation), a disaster for the agency comparable to the fall of Prosper in France. After the war Marks had some success himself in the film industry, writing screenplays and stories for at least eight films including Michael Powell’s notorious Peeping Tom (1960).

The Déricourt affair and its later contested history could, no doubt, be adapted into a compelling screen narrative, but so far it has never been filmed. According to Ulivieri, who interviewed le Carré in 2008, the writer ‘didn’t believe the reality of Déricourt’s story’, dismissing it as ‘a piece of espionage science fiction’.[8] Unfortunately, like ‘Aryan Papers’ the project remained unrealised, and no further Kubrick productions appeared until his final film, Eyes Wide Shut, in 1999.

Notes

[1] John le Carré, The Pigeon Tunnel (London: Penguin, 2016), 241.

[2] M.R.D. Foot, SOE in France (London: HMSO, 1966), 301.

[3] Sarah Helm, A Life in Secrets: Vera Atkins and the Missing Agents of World War II (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2005), 383.

[4] Stanley Kubrick Archive, University of the Arts London, SK/18/4/12.

[5] Kubrick’s books are in the archive under SK/1/1.

[6] Jan Harlan, ‘From Wartime Lies to “Aryan Papers”’, in The Stanley Kubrick Archives, ed. Alison Castle (Köln: Taschen, 2018), 816-19 (817).

[7] Filippo Ulivieri, ‘Waiting for a miracle: a survey of Stanley Kubrick’s unrealized projects’, Cinergie – Il Cinema E Le Altre Arti 12(2017), 95-115 (105). See https://cinergie.unibo.it/article/view/7349/7318.

[8] Ulivieri.